Intro

The 1893 Columbian Exposition marked the first World’s Fair

in which women were given their own explicit building to display their

accomplishments. The United States government appointed a Board of Lady

Managers, a group of women who were given government funds to construct a “Woman’s Building” and select objects to exhibit female progress throughout history. Among the items on exhibit in the building were historical objects, a library filled with volumes written by women, and artworks by female artists.

Architecture of The

Woman’s Building

The Board of Lady managers decided that they wanted a female architect to design the Woman's Building. In order to choose a designer, they held a competition that asked female architects from around the nation to

submit their potential plans. After several weeks of debate, The Board of Lady Managers

chose Sophia Hayden out of the thirteen competitors as the competition winner. Hayden was a recent graduate of

the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, having been the first woman to

graduate with an architecture degree from the institution.

|

| Photograph of The Woman's Building Glimpses of the World's Fair: Through a Camera. Black and White Photograph. Liard & Lee Publishers. Chicago: 1893. |

The Woman’s Building itself was designed was in the Italian

Renaissance style and the plan was actually based on Hayden’s senior thesis.

The interior of the building housed a 7,000 volume library containing the

written works of women, an assembly hall where women could give speeches and

gather, headquarters for various organizations, and a large hall, called the

“Gallery of Honor,” that served as a gallery for women’s art.

Art in the Woman's Building

Mary Cassatt, Modern Woman

The official guidebook to the fair was clearly no different

than the critics in its opinion of Cassatt’s piece. While the booklet spends an

entire page extolling the beauty of the lesser known MacMonnies work, it

devotes a few curt sentences to Cassatt’s mural, and refers only to her

decoration of the border, which it notes is “quite charming.”

Hutton, John. "Picking Fruit: Mary Cassatt's Modern Woman and the Woman's Building of 1893." Feminist Studies:Women's Agency: Empowerment and the Limits of Resistance, Vol. 20, No.2 (1994): 318-348.

Art in the Woman's Building

Painting at the time, like most professions, was a career

largely dominated by men. Women artists felt they needed to prove both their ability

and skill as artists in order to be accepted by their male counterparts. The

commission for a large scale painting at all was a feat at the time for female

artists. Thus, women tended to play it safe in terms of the subject matter and

style they used. Women were expected to paint allegorical, dainty, and feminine

scenes, and to use pleasing colors and soft shapes. Many women stuck to these expectations, not wanting their skill to be criticized as a result of stepping

outside these boundaries.

Six large murals inside the Woman’s Building suggested

woman’s evolution from “primitive” to modern. The goal of these murals was to

illustrate the progress made by women through history and their continued

advancement in contemporary times.

These murals were placed in a cyclical pattern

beginning on the north tympanum of the hall with Mary MacMonnies’ Primitive Woman, which showed women in

their most undeveloped uncivilized state. On the East wall, Amanda Brewster

Sewell’s mural Women in Arcadia, and

Lucia Fairchild’s mural The Women of

Plymouth, showed the advancement and skill of women made even in the past.

On the south wall, was a controversial mural by Mary Cassatt, entitled, Modern Woman. And finally, on the west

wall were two works by the sisters Lydia Emmet and Rosina Emmett Sherwood,

titled Art, Science and Literature,

and The Republic’s Welcome to Her

Daughters, which represented women in contemporary times.

Of the murals, the two that received the most attention at

the fair were MacMonnies’ Primitive Woman

and Cassatt’s Modern Woman. The

location of both works today is unknown, but black and white photograph images

give a relatively good idea of how they would have looked.

MacMonnies, Primitive Woman

|

| Mary Macmonnies, Primitive Woman. 48 x 12 feet, 1893. Present Location Unkown |

MacMonnie’s work was considered to be extremely successful

and was praised by critics and fairgoers alike. MacMonnies was a little known

American artist who specialized in landscapes and genre paintings. She was

chosen in large part because of her marriage to the artist Frederick MacMonnies,

who was designing a fountain for the fairgrounds and thus gave her easy access

to workspace and materials at the fair.

Her mural showed a pleasing scene of uncivilized villagers,

women and men both, working side by side. The imagery is described in the fair's official guidebook. Male hunters “clad in skins,” come back home

having, “just returned from the chase,” while women hold children, “carry water

jars,” and crush grapes to make wine.

The division of male and female labor is made clear in the

piece; the role of men as providers and protectors is stressed, while women are

shown as caregivers and nurturers. In her mural, MacMonnies thus strived to

portray primitive women as necessary and useful to the development of mankind,

yet still confined within the limited female sphere of the domestic maternal figure.

Critics at the time praised both MacMonnies skill and

subject. The official guidebook declared that her work “shows a true decorative

sense, a sure hand, and a fresh, joyous imagination.” The colors of the mural were cool and soft,

and her composition was pleasing to the eye. MacMonnies herself explained that

she thought that a mural should be a “superior sort of wall-paper, which gives

first and above all a charming and agreeable effect as a whole, but does not

strike the eye or disturb attention.” (source)

.jpg) |

| Mary Cassatt, Central Panel of Modern Woman 48 x 12 feet, 1893. Present Location Unknown |

Mary Cassat’s mural, on the other hand, was not so well

received by critics; she dared to push the boundaries and to create an artwork

that was not what fairgoers or contemporary reviewers expected.

Cassatt was an American painter who had come from a wealthy

family. She attended the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts in 1860 and

eventually went to Paris where she found a place with the Impressionist

painters. She was an active member of the Impressionist group from about 1879

to 1886 and was involved in the Parisian intellectual and cultural circles, a

rare feat for an American at the time. Her subjects focused mostly on Parisian and

family life. Today, she is best known for her paintings of mothers and

children. At the time, she was relatively well known in Paris and New York.

|

| Mary Cassatt, Self Portrait c. 1878 |

Cassatt chose as her subject for the mural “women picking

fruit from the tree of knowledge.” The mural depicts a group of young women in

contemporary dress gathering apples in an orchard. Twelve women in total are

represented in four groups of three, and no male figures are shown. The women

interact with one another and play instruments and dance in a bright pastoral

scene.

Critics criticized Cassat’s use of bright colors and flat

figures; they felt that this bold use of color was somehow unfeminine and out

of line for a female painter. Henry Fuller in the Chicago Record wrote that “the impudent greens

and brutal blues of Miss Cassatt seem to indicate an aggressive personality

with which compromise and cooperation would be impossible,” he continued, “Miss

Cassatt has a reputation for being strong and daring; she works with men in

Paris on their own ground.”

In stepping outside of the accepted norms and

boundaries expected of female painters, Cassatt was rejected as an unskilled

artist.

However, while at the time the subject matter and

symbolism of Cassatt’s image seemed strange and unacceptable,

recent art historians have re-examined her work and found that Cassatt’s mural

is actually a declaration of feminine intelligence and capability. In his

journal article, “Picking Fruit: Mary Cassatt’s Modern Woman and the Woman’s

Building of 1893," art historian John Hutton points out that Cassatt actually

attempts to transform the biblical narrative of Adam and Eve into a call for

female empowerment. Throughout history, the role of Eve in the garden of Eden

had been used to disparage the female role. Eve, in taking fruit from the

snake, introduced sin to humanity and was the cause of mankind’s exile from the

Garden of Eden. However, Hutton points out, that several feminist groups at the

time had slowly been working towards inverting this narrative.

|

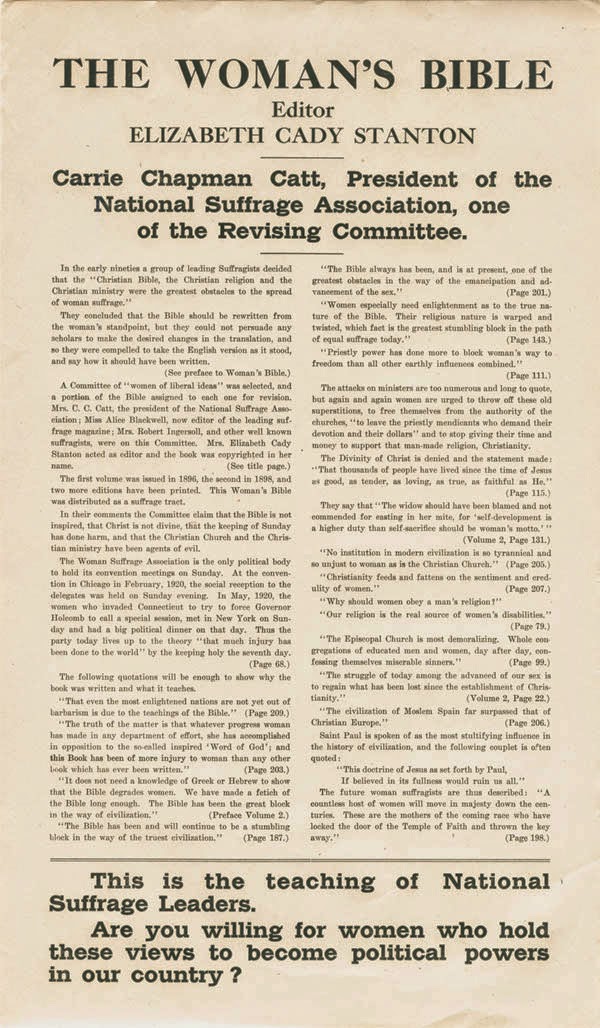

| Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Page from the Woman's Bible |

A few years

before the Chicago Exposition, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, a well known feminine

activist, had put together “The Woman’s Bible,” a document which rethought

biblical narratives in order to give women a empowering role in the text.

Stanton argued that Eve represented, not the woman who led to fall of man, but

the figure who led the human race out of ignorance and into truth. In The

Woman’s Bible she argues,“If…we accept the Darwinian theory, that the race has

been a gradual growth from a lower to a higher form of life, and that the story

of the fall is a myth, we can exonerate the snake, emancipate the woman, and

reconstruct a more rational religion for the nine-teeth century.”

Thus, in depicting modern women in contemporary dress

laboring in a field by picking apples, Cassatt may have actually been asking

contemporary viewers to rethink their conception of women through history.

Women were not gradually making their way forward from primitive times to

become more enlightened beings, but were actually always the keepers of

knowledge, and were only now able to realize their full potential in society.

That contemporary critics and viewers were unable to grasp

the symbolism of the image spoke, not to Cassatt’s inability as an artist, but

to societies inability to change the fundamental way in which women were

viewed.

Resources

Elizabeth Cady Stanton. The Woman’s

Bible: A Classic Feminist Perspective. New York: European Pub. Co., 1895.

MacMonnies,

Mary. Primitive Woman, 1893.

Cassatt,

Mary. The Modern Woman, 1893.

Mary

Cassatt. Self Portrait. Watercolor, gouache on wove paper, 1878.

Hutton, John. "Picking Fruit: Mary Cassatt's Modern Woman and the Woman's Building of 1893." Feminist Studies:Women's Agency: Empowerment and the Limits of Resistance, Vol. 20, No.2 (1994): 318-348.

Waldheim, Charles and Katerina Ray, Chicago Architecture: Histories, Revisions, Alternatives. London: The University of Chicago Press, 2005.

Wels, Susan. "Spheres of Influence: The Role of Women at the Chicago

World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893 and the San Francisco Panama Pacific

International Exposition of 1915." PhD. diss., San Francisco State University, 2015.

The Decoration of the Woman’s Building at the Columbian

Exposition. Vol. 23 No. 6 (mar. 1894)

Gaze, Delia. Concise Encyclopedia of Women Artists. Taylor

and Francis, 2001.